“Winning isn’t something that happens suddenly on the field when the whistle blows and the crowds roar. Winning is something that builds physically and mentally every day that you train and every night that you dream.”

Emmitt Smith

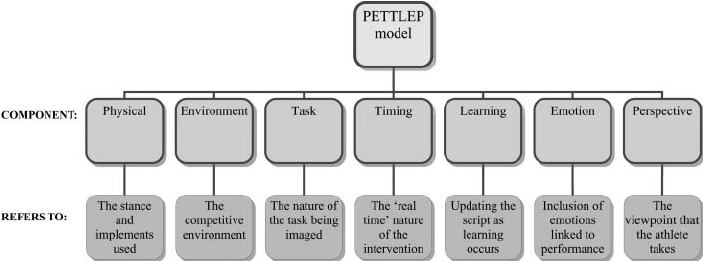

Emmitt Smith was ahead of his time when it came to visualization practices. He knew that, in order to play his best, he needed to be able to see himself do it in his mind’s eye first. Now, I am not Emmitt Smith, but I have researched a lot on peak performance. I have found the Holmes and Collins (2001, 2002) PETTLEP model is the best out there when it comes to simplifying the process of visualization.

The PETTLEP model was created to help guide those who wanted to visualize. We all know that mental reps are important, but what exactly are we supposed to be seeing? What is the BEST way to visualize? Paul S. Holmes and David J. Collins, of Manchester Metropolitan University and the University Edinburgh, UK, respectively, set seven key components in their PETTLEP approach below.

Physical

When we are visualizing things, we need to make them feel as real as possible. The closer we can get to fully experiencing every sensation of the task, the more we will feel like we have “already been there”. If we are trying to improve our pitching, we should do it with a glove, a hat and a ball. If we struggle with the swing, we should have a bat in our hands. To go even further, if there is a point you know your heart starts pounding out of control in the box or on the mound, we must practice it in our visualization. If we don’t, we will get to the game and it will feel like a totally new experience.

Environment

The environment we are talking about here is where the actual tasks are taking place. Obviously, if you are about to play in the College World Series, it is going to be hard to stand in the box at TD Ameritrade. Whenever possible, however, try to replicate the place you are going to compete. This gets your brain used to your surroundings to the point that it becomes familiar.

Task

This one is interesting. The content of your visualization should be relatable to your skillset as an athlete. If you are a high school athlete, your focus may be on watching the ball out of the pitchers’ hand and staying level with your swing. As a professional athlete, your visualization will be more advanced. You may be thinking about seeing the grip as the pitcher releases in order to buy more time with your lower half.

Timing

The timing of the visualization is really important. By this, I mean the pace and the amount of time you spend visualizing an event. If you are a starting pitcher and your visualization sessions are only five minutes, anything beyond five minutes in the game is unpracticed territory for you. This goes the same for seeing it all in slow-motion or sped up in our heads. Actions happen at game speed; visualization should be game speed as well.

Learning

The learning aspect means that as the athlete becomes more skilled, the visualization should reflect that as well. If you want to get better at bench press, you must steadily increase the weight you are visualizing yourself lifting. It is really hard to bench 200 if you are constantly benching 185 in your head. Same with what you are feeling as far as adrenaline and confidence. The more skilled you become, the more confident you should be performing those skills mentally.

Emotion

If you want to relive a moment in your head, you must relive it emotionally as well. Sports and competition are filled with emotions. We experience exhilaration when we drive in a run. We experience frustration when we have a bad call go our way. We must fully attach our emotions to the experience. It is important to calm ourselves down on the field, but off it we must make it high pressure.

Perspective

Books are often read through the first- or third-person perspective. When we visualize, we can do it in either as well. The first-person perspective is the most widely used form and is great. There can definitely be a benefit from seeing yourself do it from the stands as well. Every person is different, so it is important to find what perspective works best for you and your situation.

I encourage you to incorporate as many of these components into your visualization as possible. We want the games and competition to feel like just another day at the office. The only way to do this is to make the visualization as game-like as possible.

Tons of credit to Caroline Wakefield and Dave Smith in the Department of Psychology at Liverpool Hope University. Much of the information was from their article in the Journal of Sport Psychology in Action titled “Perfecting Practice: Applying the PETTLEP Model of Motor Imagery”. Link to the full article is here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2011.639853